Thursday, June 12, 2008

100 and Counting

It's official! As I have now passed 100 visitors to my blog, I wanted to say "thank you" to all who have stopped by and especially to those of you who have left comments. Thank you for being patient with me as I have gotten this site up and running, and I hope that you will continue to enjoy reading my architectural musings!

The Benefit of the Doubt

It is no secret that I am not exactly a fan of the Art History addition to Yale's A+A building, but lately I've been trying to give it the benefit of the doubt. Construction is coming along nicely, and the massing of the building when viewed from York Street near the Yale Repertory Theatre is actually not bad. Though I am still disappointed that the panoramic view to campus from the architecture studios has been lost with the construction of the Art History building, I have been trying to change my attitude toward the building over all and take it for what it is. After all, it is a tough site for any architect, and who can really compete with Rudolph's A+A and across the street from two beautiful Kahn museums!

It is no secret that I am not exactly a fan of the Art History addition to Yale's A+A building, but lately I've been trying to give it the benefit of the doubt. Construction is coming along nicely, and the massing of the building when viewed from York Street near the Yale Repertory Theatre is actually not bad. Though I am still disappointed that the panoramic view to campus from the architecture studios has been lost with the construction of the Art History building, I have been trying to change my attitude toward the building over all and take it for what it is. After all, it is a tough site for any architect, and who can really compete with Rudolph's A+A and across the street from two beautiful Kahn museums! That was until I saw this. No, not the silly construction worker, but the window he is posing in. I have been wondering about this window for a few weeks as I have watched it being built. When it first went up, I thought that it looked like it was not properly installed or they were still working on it. Then came the triangular metal panel underneath which sealed the deal: this thing is here to stay.

That was until I saw this. No, not the silly construction worker, but the window he is posing in. I have been wondering about this window for a few weeks as I have watched it being built. When it first went up, I thought that it looked like it was not properly installed or they were still working on it. Then came the triangular metal panel underneath which sealed the deal: this thing is here to stay.You might think this is just a window and that it is no big deal, but the window is just a symptom of a larger issue. This key feature on the facade continues to reinforce one of my early criticisms of the building: the addition is simply too "busy" to provide a neutral and respectful backdrop for the A+A. It is just another random feature on a jumbled composition of forms with too many ideas vying for attention at once.

Call me a Modernist (don't worry, I won't be offended), but Rudolph's and Kahn's buildings are so much better than the Art History addition that I just cannot seem to get over it. True, in the scheme of things, the Art History addition is much better than a lot of architecture in the world. But a lot of architecture is not next to three world-class buildings by two of the world's greatest Modern architects! Because of this, Yale University and Charles Gwathmey should have been held to a higher standard of design. But in my humble--but firm--opinion, it appears that the result of their collaboration in this case may end up being as bad as I had feared.

Call me a Modernist (don't worry, I won't be offended), but Rudolph's and Kahn's buildings are so much better than the Art History addition that I just cannot seem to get over it. True, in the scheme of things, the Art History addition is much better than a lot of architecture in the world. But a lot of architecture is not next to three world-class buildings by two of the world's greatest Modern architects! Because of this, Yale University and Charles Gwathmey should have been held to a higher standard of design. But in my humble--but firm--opinion, it appears that the result of their collaboration in this case may end up being as bad as I had feared.

Tuesday, June 10, 2008

About the Images

Thanks, James, for your comments on image licensing and intellectual property on the internet. A your suggestion, I have now figured out how to place an image on my blog with a link rather than having to download the image first. Hopefully this system will allow me to show images that are not explicitly mine while still still leaving full control in the hands of the images' author (or at least, in the hands of the original person who "borrowed" and posted it!). Either way, I suppose I have rationalized enough at the moment to clear my conscious. Sigh.

And a note for the visually-inclined: I have gone back and inserted some images into a few of my previous posts. Happy (re)reading!

Creative Commons

When I started my blog, I made the conscious decision to try to be sensitive to the use of copyrighted images. I promised myself that I would only upload photographs or images that I had generated myself or that I was given permission to use, thus steering away from the rampant internet image “borrowing” that I face (and, dare I say, participate in) at work.

As another way to show that I was sensitive to this issue, I also included information on my blog’s sidebar on “Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works” licensing provided by Creative Commons. This was simply my way of showing my readers that I had the right to show all of the images posted on my blog and that I was not posting any copyrighted images without permission. I also hoped, though I have no real way of policing this, including a Creative Commons license would prey on people’s conscious and remind them that they should not download the images from my blog and use them without my knowing.

I thought this was all well and good until I was having a conversation with a friend the other day about my blog. I thought my position was pretty straightforward, but I realized that it is not so clear cut. For instance, one might argue that the internet is entirely public domain, and that anything posted online, even for an instant, has been forever placed in the hands of the public. Though this is a little extreme for me, I do get the point. I am not a photographer and am not making a living off of photography, so I do not have a great deal at steak by protecting my images, yet I have this urge to do so.

So, now I want to ask you, what do you think? If you feel strongly one way or another about image licensing on the internet, I would love to hear from you. Please use the “comments” function just below this post to share your thoughts. Thanks!

As another way to show that I was sensitive to this issue, I also included information on my blog’s sidebar on “Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works” licensing provided by Creative Commons. This was simply my way of showing my readers that I had the right to show all of the images posted on my blog and that I was not posting any copyrighted images without permission. I also hoped, though I have no real way of policing this, including a Creative Commons license would prey on people’s conscious and remind them that they should not download the images from my blog and use them without my knowing.

I thought this was all well and good until I was having a conversation with a friend the other day about my blog. I thought my position was pretty straightforward, but I realized that it is not so clear cut. For instance, one might argue that the internet is entirely public domain, and that anything posted online, even for an instant, has been forever placed in the hands of the public. Though this is a little extreme for me, I do get the point. I am not a photographer and am not making a living off of photography, so I do not have a great deal at steak by protecting my images, yet I have this urge to do so.

So, now I want to ask you, what do you think? If you feel strongly one way or another about image licensing on the internet, I would love to hear from you. Please use the “comments” function just below this post to share your thoughts. Thanks!

Friday, June 6, 2008

Playing Favorites

I do not get asked this question much anymore but early on in my architectural education, whenever someone would hear that I was studying architecture, they would invariably ask me who my “favorite” architect was. This dreaded question was frequently followed by “You must love Frank Lloyd Wright.” No matter who asked me, I always admitted that, though I did appreciate Wright’s work, I could not count him as my favorite. At the time I was on a Mies van der Rohe kick so I would generally go into a discussion of Mies and his brilliant contribution to the legacy of Modern architecture. This response usually left a puzzled and somewhat disappointed look on my questioners face: they had never heard of this Mies character, and how could I not love Frank Lloyd Wright!

I do not get asked this question much anymore but early on in my architectural education, whenever someone would hear that I was studying architecture, they would invariably ask me who my “favorite” architect was. This dreaded question was frequently followed by “You must love Frank Lloyd Wright.” No matter who asked me, I always admitted that, though I did appreciate Wright’s work, I could not count him as my favorite. At the time I was on a Mies van der Rohe kick so I would generally go into a discussion of Mies and his brilliant contribution to the legacy of Modern architecture. This response usually left a puzzled and somewhat disappointed look on my questioners face: they had never heard of this Mies character, and how could I not love Frank Lloyd Wright!The first Mies building that I ever visited in person was the Seagram Building in New York City. In fact, my first visit to the Seagram Building played a role in my love story with Kim. I like to joke that the day we saw the Seagram Building together was the day I knew that she really loved me.

Let me explain.

Kim and I met at church camp after our junior year of high school. We made fast friends that summer but returned to our respective high schools in neighboring districts for our senior year. After not speaking for several months, we got back in touch in December and started dating during the spring before graduation. Since we had each already decided where we would be going to college before we started dating, we were faced very quickly with the prospect of a long-distance relationship: I would be in Atlanta—Kim would be near Philadelphia.

The way the Seagram story sticks in my memory is this: during the summer between high school and college, Kim and I took a day trip from our homes in Pennsylvania to New York City. Honestly, I do not remember many details about that day except for the weather and the Seagram Building. By the time we were preparing to leave the City, the day had gotten gray and rainy, but I had wanted to see the Seagram Building and Kim agreed that we should walk to see it before returning home.

The way the Seagram story sticks in my memory is this: during the summer between high school and college, Kim and I took a day trip from our homes in Pennsylvania to New York City. Honestly, I do not remember many details about that day except for the weather and the Seagram Building. By the time we were preparing to leave the City, the day had gotten gray and rainy, but I had wanted to see the Seagram Building and Kim agreed that we should walk to see it before returning home.So there we were, in a new relationship, facing the inevitable long-distances that would separate us during college, walking arm-in-arm under one umbrella along block after gray block of wet city to reach a glass-clad skyscraper designed by a dead German-American architect who was by no means a household name and that most people would not give a second glance. We arrived to the Seagram Building for the first time together, but the important thing is not that I remember the building but the walk in the rain with the wonderful woman who would several years later become my wife.

Sometimes we do strange or even silly things for those that we love just because we love them. I know that at the time, before she learned to better appreciate my eye for Modern architecture, visiting the Seagram Building in the rain was one of those moments for Kim. I continue to be astounded by all the silly but selfless things she does for me to make me happy.

We left for college that fall. We became fond patrons of instant messaging and AirTran’s discount fares between Atlanta and Philadelphia. We were married four years later, a week after graduation, and we left for Yale and New Haven only a few months after that. We celebrated 10 years together in March and our 6th anniversary in May.

Thursday, June 5, 2008

A Strange Paradox

"All forms that create beauty have a function." (Oscar Niemeyer)

Yesterday on a flight to Calgary I read The Curves of Time: the memoirs of Oscar Niemeyer. First published in English in 2000, the book was recently re-released in December of 2007 to celebrate Niemeyer’s 100th birthday.

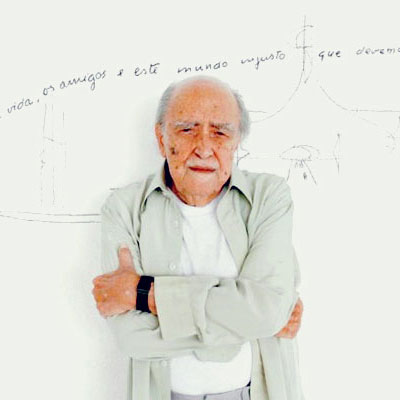

Yesterday on a flight to Calgary I read The Curves of Time: the memoirs of Oscar Niemeyer. First published in English in 2000, the book was recently re-released in December of 2007 to celebrate Niemeyer’s 100th birthday.I have admired Oscar Niemeyer’s work for quite some time. At 100 years old and still practicing in his native Brazil, he is the last surviving master of Modern architecture, and the tenacity of his spirit alone, not to mention his beautiful architecture, is enough for me to be able to count him among my architectural “heroes.”

I do not even fully understand myself why I love Niemeyer’s work so much. In many ways, it presents a strange paradox. I love it because it is unique yet contextual, massive yet light, rational yet sculptural, irrational yet beautifully engineered, simple yet complex, diagrammatic yet well-developed, messy yet clean, clunky yet gentle. I love it because it is completely Modern. I love it because it is uninhibited. I love it because it is fun.

And like his architecture, Niemeyer himself is somewhat of a paradox. He writes in the forward to the 2007 edition, “On re-reading this book, I feel that it uncovers two distinct personas. One looks on the bright side of life and sees the fun part of it that has always attracted me. The other has a pessimistic view of life and society in general, and is angered by the injustices of this world.”

Throughout his rambling prose, which is superficially about architecture but mostly about his incredibly rich and colorful life, Niemeyer’s most poignant writing is not about his architecture, but about his friends, his family, his travels, his hopes and fears for the world. His gentle words of sorrow are the ones that touched my heart the most. “There are elements of the past that I have never forgotten. Family, my beloved parents, friends who were so close . . . I cannot help crying, quietly, slowly, tenderly, with melancholy. I close my eyes and a strange serenity settles over me, as if I were off to meet them all again. . . . What bothers me is not life’s few rough edges, but the tremendous suffering of the destitute confronted with the indifferent smiles of the well-to-do.”

I have had a long-time dream of meeting Oscar Niemeyer someday, not only because of my admiration for his work, but also because of the contribution he has made to architecture. Not only did he help to release Modernism from its restrained European roots, but his architectural legacy in Brazil will continue to live on long after he is no longer adding great buildings to its number. I know that meeting him now near the end of his extraordinary career and while I am still taking my own baby steps in architecture would be a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Niemeyer is the last representative of a great Modern tradition. I have no doubt that I will someday have the opportunity to travel to Brazil to see Niemeyer's work first-hand, but I understand with a bit of sadness that my chances of meeting this great architect in person dwindle with each passing year.

I have had a long-time dream of meeting Oscar Niemeyer someday, not only because of my admiration for his work, but also because of the contribution he has made to architecture. Not only did he help to release Modernism from its restrained European roots, but his architectural legacy in Brazil will continue to live on long after he is no longer adding great buildings to its number. I know that meeting him now near the end of his extraordinary career and while I am still taking my own baby steps in architecture would be a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Niemeyer is the last representative of a great Modern tradition. I have no doubt that I will someday have the opportunity to travel to Brazil to see Niemeyer's work first-hand, but I understand with a bit of sadness that my chances of meeting this great architect in person dwindle with each passing year.I was initially a little hesitant to read Niemeyer’s memoir because I did not want the truth of the man to cloud my admiration for his work. But after reading his beautifully willful and wandering story, I am even more moved with admiration for his sympathetic soul. I am drawn to the exuberant artist, the melancholy soul, the political dissident, the lover of mankind, the sympathizer with the oppressed, the creator of beauty.

"I have always argued for my favorite architecture: beautiful, light, varied, imaginative, and awe-inspiring." (Oscar Niemeyer)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)